Carbon Capture Geoengineering 2050

The Hidden Dangers of Massive Carbon Dioxide Pipelines and Underground Sequestration

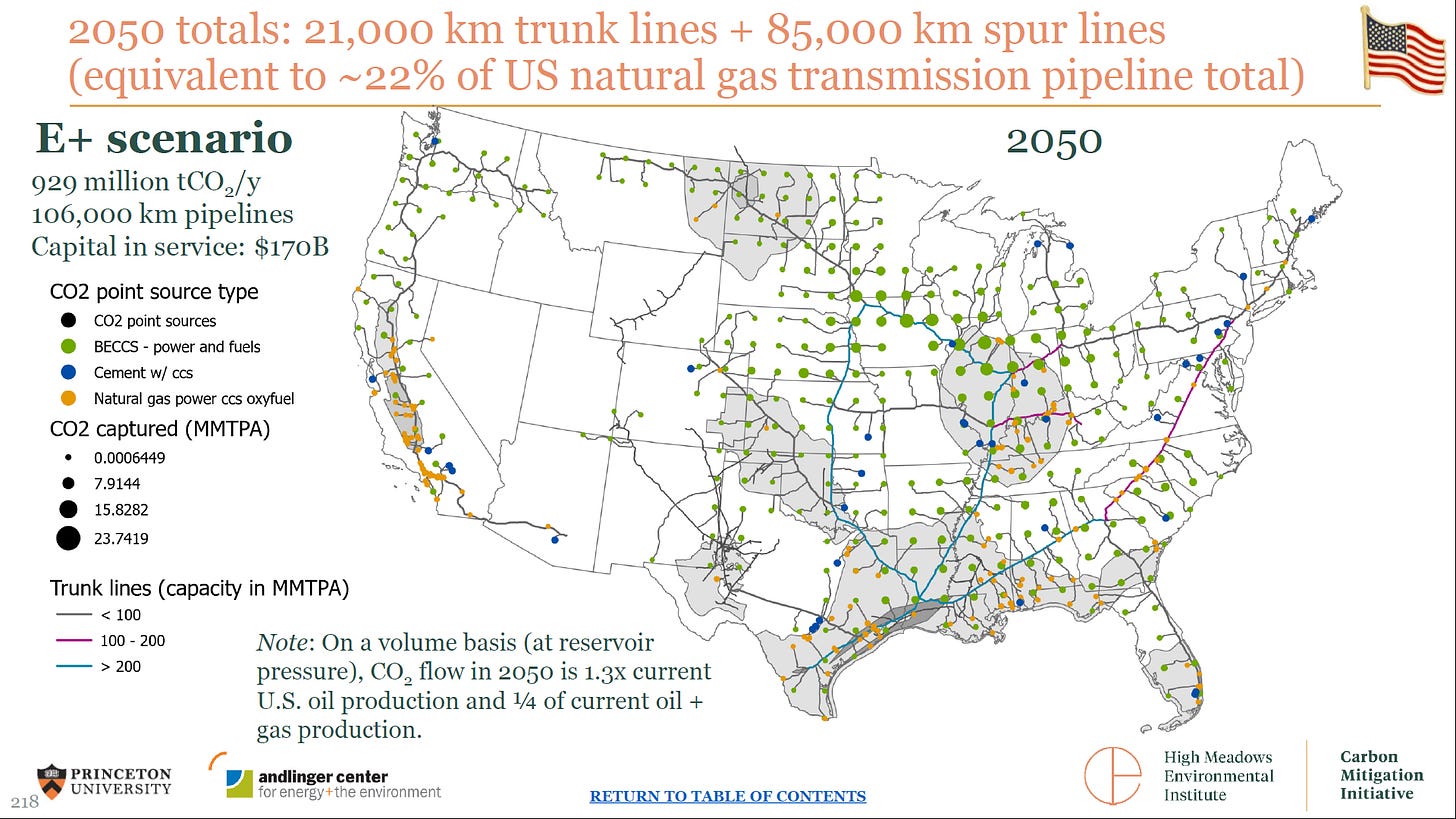

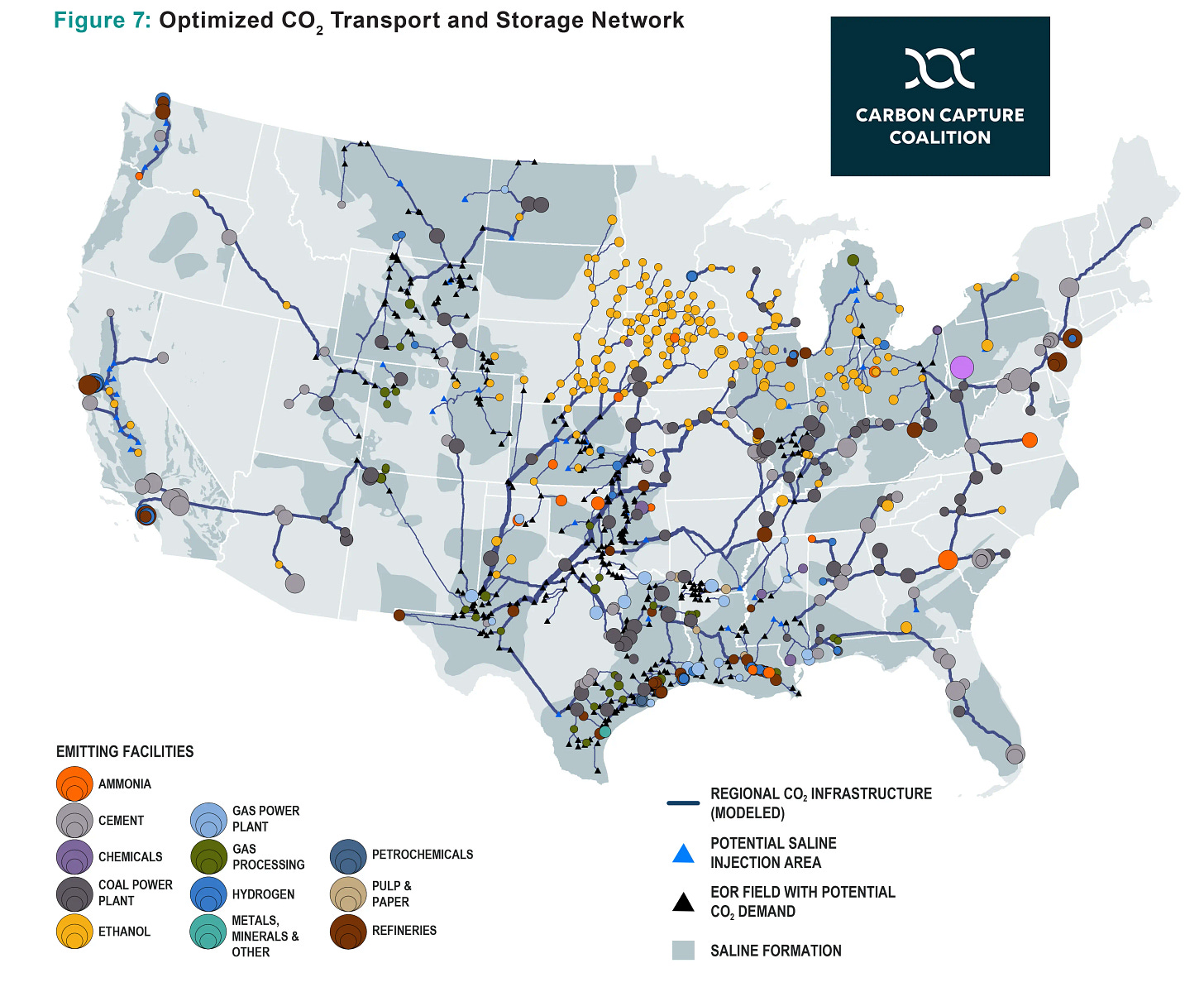

Imagine a sprawling network of 48-inch pipelines, paired in twos and pressurized up to 3,000 pounds per square inch (PSI), crisscrossing the United States to transport liquid carbon dioxide (CO2) from capture points to sequestration or reuse sites hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away. This ambitious proposal, part of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) efforts, is pitched as a solution to climate change. Yet, beneath its promise lie significant risks and ethical concerns that demand closer examination.

We’ll dive into the dangers of these high-pressure CO2 pipelines, the contentious use of eminent domain to seize land across all fifty states, the environmental hazards of pumping CO2 into saline formations underground, and the broader debate over whether carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is a viable alternative to transitioning to non-carbon emitting power sources.

Eminent Domain: A Threat to Property Rights and Indigenous Lands

The construction of these massive CO2 pipelines hinges on eminent domain—the legal authority of the government to take private land for public use, with compensation. However, applying this power to CCS projects raises serious questions about fairness and federal overreach.

Private Citizens’ Lands at Risk: Landowners across the U.S., such as those in Nebraska highlighted by Bold Nebraska, are fighting against what they see as an abuse of eminent domain. They argue that these pipelines primarily benefit private corporations rather than the public, challenging the justification for seizing their farms, homes, and livelihoods. With plans to span all fifty states, the scale of land acquisition could spark widespread disputes and legal battles.

Endangering Indigenous Lands: For Indigenous communities, the stakes are even higher. These pipelines could cross sacred sites or infringe on treaty-protected lands, echoing a long history of federal disregard for Indigenous sovereignty. The potential violation of these rights adds a profound ethical dimension to the debate, as noted in discussions on sites like Deceleration News.

Federal Overreach and Explosive Risks: Beyond property rights, the high-pressure nature of these pipelines—operating around 3,000 psi—introduces the danger of explosive failures. A rupture could devastate rural landscapes, homes, and communities, especially in areas ill-equipped for emergency response. This federal push to prioritize CCS infrastructure over citizens’ rights and safety underscores the tension between climate goals and human costs.

The use of eminent domain for such a vast and risky project prompts a critical question: Do the uncertain benefits of CCS justify endangering private and Indigenous lands?

[ NOTE: While I do not agree with some of the assertations of Vice or comments made near the end of this video, I nonetheless submit to you to story of Standing Rock and my native brothers and sisters who fought to oppose pipelines on sacred land, and lost. Water is life! ]

The Dangers of High-Pressure CO2 Pipelines: A Catastrophe Waiting to Happen?

These 48-inch pipelines, designed to carry supercritical CO2 (a dense, liquid-like state), are engineering marvels—but they’re also potential disasters. Operating at extreme pressures, they pose unique and severe risks.

Asphyxiation Hazards: A stark example unfolded in 2020 in Satartia, Mississippi, when a CO2 pipeline ruptured. The invisible, odorless gas displaced oxygen, hospitalizing dozens of residents who struggled to breathe. As reported in various accounts, including insights from YouTube analyses, emergency services were overwhelmed, highlighting the acute danger of CO2 leaks near populated areas.

Explosive Failures: The combination of high pressure and large diameter amplifies the threat. A breach could trigger rapid decompression, potentially causing explosions, hurling debris, and creating craters. Unlike natural gas pipelines, CO2 leaks are harder to detect without specialized equipment, increasing the risk of undetected disasters. The Energy.gov report on CO2 pipeline infrastructure notes the need for stringent safety measures, yet questions remain about their adequacy for such an expansive network.

With thousands of miles of pipelines proposed, the potential for human and environmental harm is alarming, particularly in rural regions where response capabilities are limited.

[ See the original video of an 8 inch carbon dioxide rupture here, now imagine an explosion 6 times larger! Starts at 11:18 in the video below ]

Underground Sequestration: Environmental Risks Below the Surface

Once transported, the CO2 is injected into saline formations underground for long-term storage. While this aims to lock carbon away, it introduces significant environmental uncertainties.

Earthquakes (Induced Seismicity): Pumping CO2 into geological formations can destabilize fault lines, triggering earthquakes—a phenomenon known as induced seismicity. Similar effects have been documented with fracking wastewater injection, and the Princeton Net Zero America annex warns of comparable risks with CO2 sequestration. Seismic activity could damage infrastructure or release stored CO2, undermining the entire effort.

Poisoning Aquifers: A major concern is the risk of CO2 leaking into groundwater. When CO2 dissolves in water, it forms carbonic acid, lowering pH levels and potentially rendering aquifers undrinkable. This threat to drinking water supplies, emphasized in critiques from Food and Water Watch, could devastate ecosystems and communities reliant on these resources.

Additional Risks: Other hazards include land subsidence (sinking ground) and the possibility of CO2 escaping through geological faults, either re-entering the atmosphere or causing unforeseen ecological damage. The long-term stability of these storage sites remains unproven, leaving environmental safety in question.

These risks challenge the narrative that underground sequestration is a clean, permanent solution, revealing a gamble with our planet’s water, land, and stability.

Carbon Dioxide Removal vs. Non-Carbon Emitting Power Sources: Pros and Cons

The debate over CCS and CDR often pits emission reductions through climate engineering against mitigation via non-carbon emitting power sources like renewables. Each approach has its advocates and detractors.

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) and CCS

Pros:

CCS allows continued use of fossil fuels while capturing emissions, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors like cement and steel, as championed by the Carbon Capture Coalition.

Federal incentives, such as the 45Q tax credit, make it economically appealing, supporting rapid deployment.

It’s framed as a bridge technology to buy time for broader decarbonization efforts.

Cons:

It’s costly and energy-intensive, diverting resources from cleaner alternatives.

Critics, including over 150 groups cited by Food and Water Watch, argue it’s a “false solution” that entrenches fossil fuel dependency rather than eliminating it.

The safety and environmental risks of pipelines and sequestration cast doubt on its long-term viability.

Transitioning to Non-Carbon Emitting Power Sources

Pros:

Renewables (solar, wind) and nuclear power directly reduce emissions by replacing fossil fuels, offering a sustainable, root-cause solution.

Long-term benefits include cleaner air, reduced carbon output, and energy independence, as outlined in studies like the Princeton Net Zero America report.

Cons:

The transition is slow, costly, and faces challenges like intermittency (e.g., solar and wind depend on weather) and the need for advanced storage solutions.

Scaling renewables to meet global demand requires significant infrastructure investment and time.

Emission Reductions vs. Climate Engineering

CDR as Climate Engineering: CCS mitigates emissions post-combustion, a form of climate engineering that manages symptoms rather than curing the disease. It’s a reactive approach with inherent risks, as seen in pipeline and sequestration concerns.

Mitigation via Renewables: Transitioning to non-carbon sources is proactive, reducing emissions at the source. While slower, it avoids the uncertainties of geoengineering and aligns with a fossil-fuel-free future.

The Zero Emissions Platform highlights CCS’s role in emission reductions, but many argue that investing in renewables offers a safer, more enduring path.

Conclusion: A Call for Awareness and Action

A Princeton study found that most Americans are unaware of CCS technologies and their implications. This knowledge gap is dangerous, as decisions about these massive pipelines and sequestration projects will shape our environmental and social landscape for decades.

Before we commit to this vast infrastructure, we must weigh the risks—land seizures, explosive pipeline failures, and environmental harm—against the uncertain benefits. Is CCS a necessary stopgap, or a risky distraction from the urgent need to shift to renewables? The evidence suggests that prioritizing non-carbon emitting power sources, despite its challenges, is the wiser, more sustainable choice.

It’s time for the public to engage, question the establishment narrative, and demand solutions that safeguard our lands, waters, and future. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

Get The Facts!

The real question is: Is carbon capture even necessary?

Additional Resources

Geoengineering technologies and approaches - Carbon Dioxide Removal | Geoengineering Monitor

BECCS carbon credit sales hit record levels despite increasing environmental and economic concerns | Geoengineering Monitor

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) Geoengineering Map | Geoengineering Monitor

Connect With ClimateViewer

Attack Ideas, Not People

❤️ you, mean it.

Jim Lee

Are you concerned about CO2 capture, pipes, and infrastructure?

Do you want me to cover this topic more often?

Have you already seen these projects in your area? Let me know!

Top 8 Reasons to Oppose Risky Carbon Pipelines

https://boldnebraska.org/no-carbon-pipelines/

We need MORE CO2 in the environment, not less. The earth has been greening from the very small additional amounts of carbon dioxide.

When CO2 levels decrease to slightly less than what is available now, life on the planet dies.

WE humans are the carbon they want to reduce.